Insyte and Resources

How can you solve your data quality areas of pain using the international data quality standard, ISO 8000?

Part 4

Creating your own Catalogue Item?

How do you create a quality catalogue item?

In part – 3 we discussed that one of the keys to creating a catalogue item with the best possible data quality is to add the most appropriate data type to each property in your data specification and where possible, to avoid the use of string fields. We will now look at the best way of adding the values to the data specification, and we will do this from the perspective of a manufacturer creating an item of production. We defined an Item of production in part – 3 as “a specification defined by the manufacturer”.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, manufacturers design and build products to a published standard. Most international standards such as ISO, IEC, ANSI, API, ASME, etc. have terms and associated definitions written into the individual standard. These standards often include a list of the allowable values for a given property of the items that is the subject of the standard. It is straightforward therefore, for manufacturers to collate a corporate dictionary using terms from the standards they work to.

Helpfully, ISO and IEC have sites where you can search on-line for authoritative terms and definitions:

- ISO Online browsing platform: available at https://www.iso.org/obp

- IEC Electropedia: available at http://www.electropedia.org/

The values however, are not readily available from these sites, and would have to be extracted from the relevant standard and added to your corporate dictionary, as in the example of ISO 15, but it is worth the effort; the inconsistent use of values is the biggest single cause of data quality issues.

The units of measure should reflect the actual units in which the product was designed, not a conversion of the measurement. If an item is designed to have an outside diameter of 30mm, it should not be stated as 1.1811”, the item was not manufactured to a tolerance associated with this inch measurement. The same applies in reverse, if an item was designed with a bore size of 1”, it should not be stated as 25.400mm. The design unit of measure should always be respected. Converting between measurement systems is more than likely to lead to data errors.

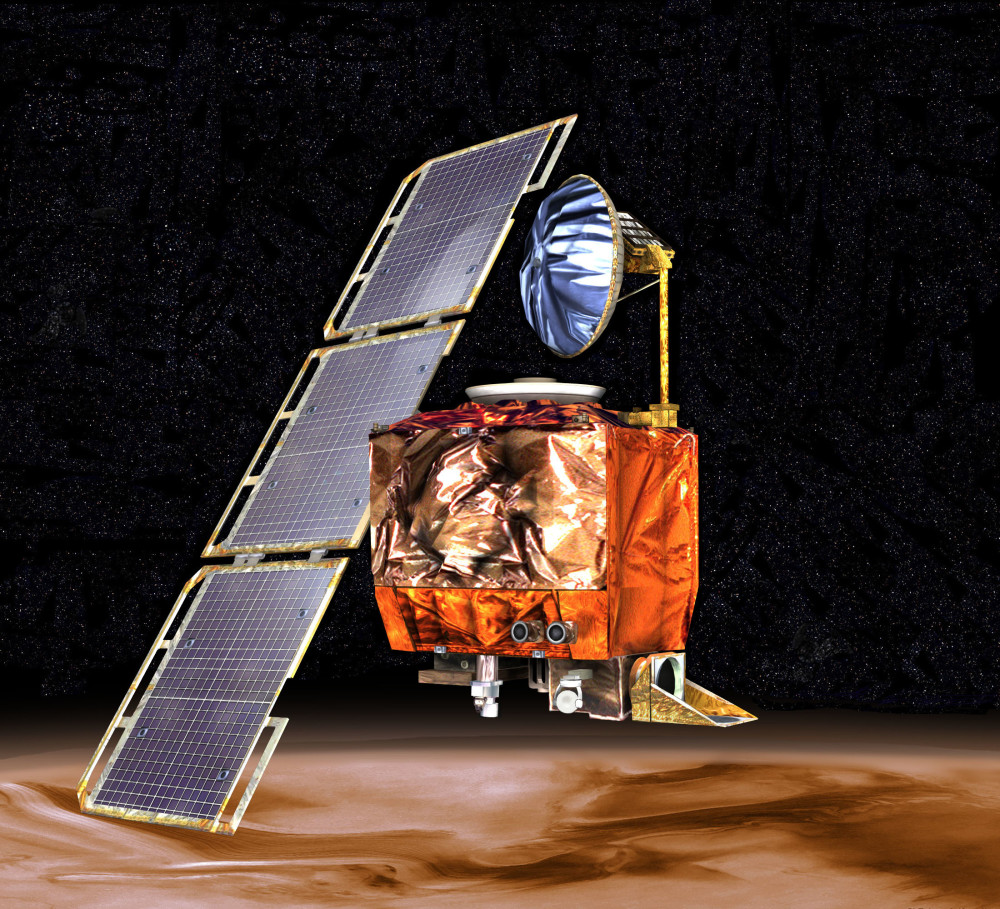

The Mars Climate Orbiter mishap is a classic example. According to the article linked, the cause of the error turned out to be a discrepancy between Lockheed Martin’s software, which generated results in U.S. customary units, and NASA’s, which was designed to accept metric units. Consequently, outputs in pound-seconds were taken as inputs expected in newton-seconds.

The issue of a single field for both the value and the UoM discussed above, more normally occur in end-user systems where product data is entered in directly, or via an upload from a data cleaners system. If you employ an external data cleansing service, you should be sure to examine how these fields are configured in their software, and how it is exported and exchanged and imported into your own system.

When selecting master data management software, besides of course ensuring that the system can produce ISO 8000 compliant data, it is also important to confirm that the property values and the units of measure (UoM) are stored in different fields in the database. Having both the value and the UoM in the same string field is another common cause of poor data quality. By having this structure, you are trying to manage two different elements and you are effectively multiplying the chances of data inconsistency, 30mm will easily end up being a mixture of 30mm, 30 mm, 30m/m, 30MM, within the data set you are managing. The most common data quality failures are found in the values and the units of measure.

The summary for this section of part 4 is: ISO 8000 states that the key to good quality data is managing data from the “bottom up”, i.e., from the smallest meaningful elements, the property value and the unit of measure.

How can I render short and long descriptions for my material masters from items of production generated by multiple organizations?

Up to this point we have explained the stages involved in creating a catalogue item from the perspective of the manufacturer. From this point forward, we are changing the focus of the conversation to the end-user, and how as an end-user, you can manage catalogue items from multiple manufacturers.

Traditionally, most end-users have tackled the issue of normalizing master data by using third-party cataloguing companies who provide specification templates to create items of supply. For those of you that have been through this process I am sure you will recall many “happy” hours spent discussing which of the many (semantically identical) terms that are used in your organization should be used in those templates. Frequently, the decisions are made by an actor who was not necessarily the data user, this often leads to a tense atmosphere in future discussions. You will also have probably spent time in the same meetings discussing the order in which the properties in the specification temple should appear. As we discussed in the various parts of this series, this type of discussion is, thankfully, consigned to history if you adopt the process based on the standards we are discussing such as the concept dictionary. Cataloguing at source (C@S), is a key part of this strategy, and is discussed in more detail in part – 5 of this series.

It is a common belief that the only way of rendering a short description is by controlling the format and order of the data specification. This method of creating short descriptions is a symptom of the constraints imposed by certain master data management systems. It is false to assume that the data receiver needs to be the creator of that data specification.

When cataloguing at source, short descriptions are rendered from the ISO 8000 compliant catalogue item provided by the manufacturer. A short description is created by selecting the desired property values that suit your requirement within the constraints of the system you are managing. Some software packages are more flexible than others when it comes to this level of control. The three key variables that normally form a short description are; a class name (or a controlled abbreviation of the class name); property value pairs (along with their unit of measure and controlled abbreviations/symbols); and most importantly, the ISO 8000-115 identifier. The figure below demonstrates an example of controlling the format of a short description using these variables. This particular example is from KOIOS Master Data using their software suite.

“In the KOIOS Master Data software the user can create a general short description format to be applied to all catalogue items and can also set short description formats per class. An end-user may want to describe particular classes in a different way than others. This feature of the KOIOS software allows greater flexibility when describing catalogue items.

In addition to this, as the KOIOS software uses more granular class names, you can format the short description of a group of catalogue items by using the same class abbreviation. For example; the abbreviation for the classes; deep grooved ball bearing; angular contact ball bearing; and tapered roller bearing, can all be BEARING, meaning that their short descriptions are consistent and meet the constraints of the short description field.“

Matt Fancourt COO at KOIOS Master Data

Enterprise systems impose character limits on short description fields which constrain the user. Therefore, it is important to have rules in place should the short description extend beyond this character limit.

Long descriptions (sometimes referred to as PO text) can also be generated from the manufacturer’s catalogue item when cataloguing at source. If the data delivered is ISO 8000-110 compliant as an XML file, then the data can probably be imported directly into the long description, or specification field. As this data has the provenance of the manufacturer, storing this data in this format greatly reduces the chances of ordering an incorrect item or service.

In part 1 of the series, we explained the role that data dictionaries play in improving your data quality. In part 2, we explained the role of the data specification in improving data quality. In part 3, we explained how to create a data specification in a way that ensures data quality is built into the final master data record. In this part, part 4, we explained how to create a catalogue item, and how to render short and long descriptions from that catalogue item. In part 5, the last part of this series, we will explain and how cataloguing at source can simultaneously cut costs and increase the quality output of your data cleansing or data onboarding project.

To sum the first four parts in this series, in order to improve the quality of your data:

- you shall use a data dictionary with an international registration data identifier (IRDI) for each data dictionary entry;

- your data specifications shall reference a data dictionary;

- your data specifications shall have appropriate data types with which to control the values;

- you must manage data from the “bottom up”, i.e., from the smallest meaningful elements, the property value and the unit of measure

About the author

Peter Eales

Chief Executive MRO Insyte

Peter Eales is a subject matter expert on MRO (maintenance, repair, and operations) material management and industrial data quality. Peter is an experienced consultant, trainer, writer, and speaker on these subjects. Peter is recognised by BSI and ISO as an expert in the subject of industrial data. Peter is a member ISO/TC 184/SC 4/WG 13, the ISO standards development committee that develops standards for industrial data and industrial interfaces, ISO 8000, ISO 29002, and ISO 22745, and is also a committee member of ISO/TC 184/WG 6 that is developing the standard for Oil and Gas Interoperability, ISO 18101.

Peter has previously held positions as the global technical authority for materials management at a global EPC, and as the global subject matter expert for master data at a major oil and gas owner/operator. Peter is currently chief executive of MRO Insyte, and chairman of KOIOS Master Data.

Peter also acts as a consultant for ECCMA, and is a member of the examination board for the ECCMA ISO 8000 MDQM certification.

ECCMA is a membership organization and is the project leader for ISO 22745 and ISO 8000 KOIOS Master Data is a world leading cloud MDM solution enabling ISO 8000 compliant data exchange MRO Insyte is an MRO consultancy advising organizations in all aspects of materials management