Insyte and Resources

SPIR’s: are they worth the paper they’re written on?

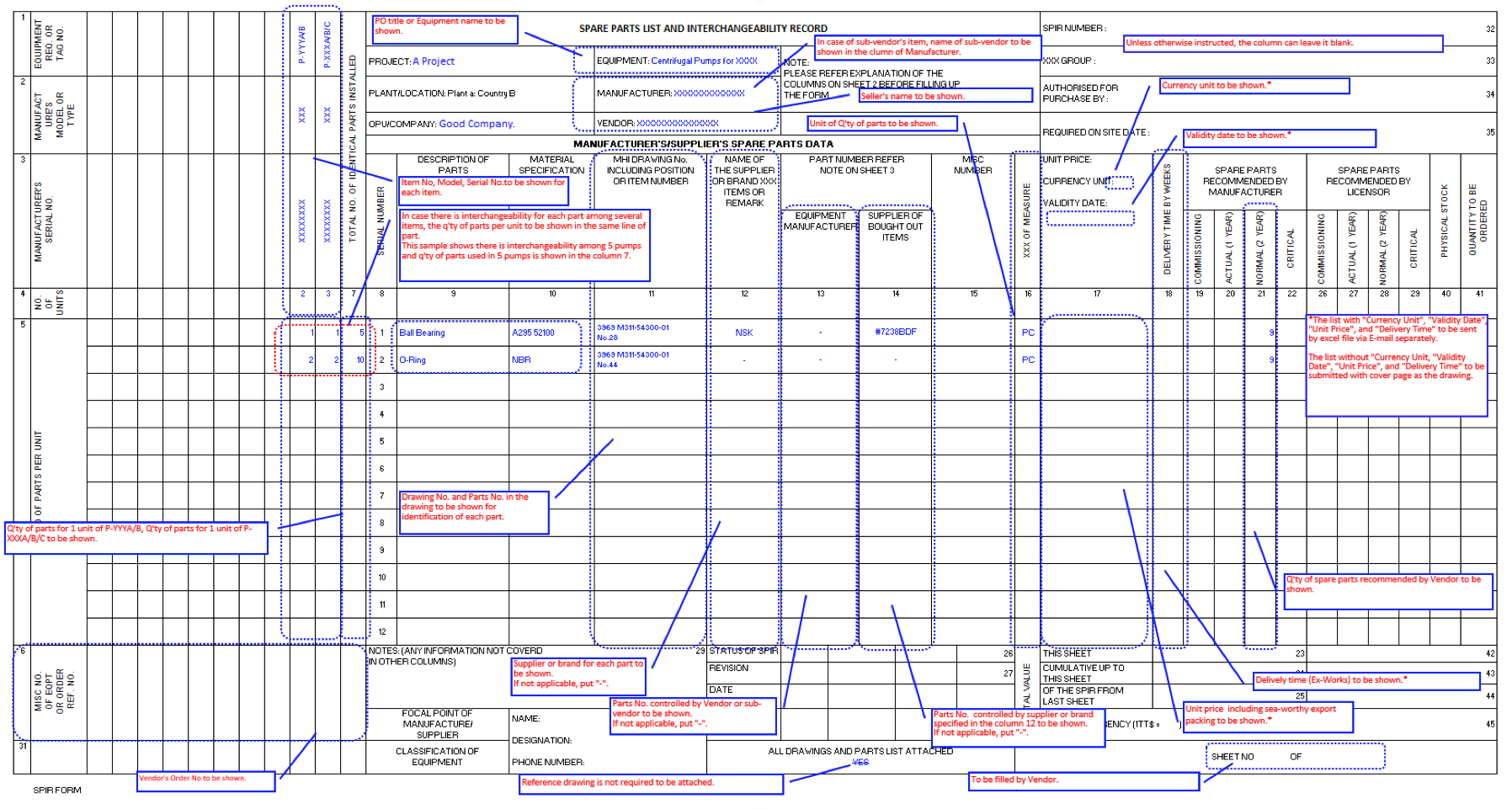

ABSTRACT: Oil and gas upstream projects typically extract material requirements from Spare Parts Interchange Lists (SPILs), sometimes referred to as Spares Parts Interchange Records (SPIRs) or Recommended Spare Parts List (RSPL). These lists are supplied to the owner / operator (O/O) at handover by the Engineering Procurement Contractor (EPC) having been supplied to the EPC by the manufacturer or the vendor of the equipment. In this article, Peter Eales provides an analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of this type of document, and questions why in the era of digital data this format is still widely used.

There are a number of issues for plant operators that arise from the use of SPIR documents in oil and gas projects. The release of these documents by the EPC is often left until the very end of the project, or not at all, despite financial penalty clauses being inserted in the contracts. This is a real challenge to the operator who wants to reduce the operating risk by purchasing long lead items early enough, and those who want to calculate the size of warehouse they require in a greenfield project.

The format of the SPIR is frequently inconsistent; effectively being a paper form that has been recreated onto a spreadsheet and edited many times. In the end it resembles nothing much more than an optimistic vendor order form. Certainly, it is an incredibly difficult document to extract data from, and as no two forms are constructed in the same way and often have merged cells. Extracting a complete project worth of data is a costly exercise in terms of both manpower and time.

These documents have many drawbacks: they are not extractable; contain only a brief description of the product, often just a noun; they take no account of the equipment criticality; they take no account of the O/Os maintenance capability, or their spares and repair strategy, such as repair or replace. Data quality is extremely poor in these types of documents. In this example, from a single 62-line SPIR document, O-Ring is described four different ways. The shore hardness is also missing from the details, making it impossible to safely order the part from another supplier. For consumable items, it is common for the original part manufacturers name to be omitted from the document.

I also take issue with the spares actually listed on the form. Interpretation of what constitutes two years operating spares vary from manufacturer to manufacturer. Some list only basic consumables, as in their opinion, that is all that is required in the first two years, some list a full production BoM (Bill of Materials) that includes such items as pump casing. Neither approach is much use to the analyst trying to decide what spares to stock in the plant or organise an on-demand local supply for.

The companies that design and manufacture equipment rarely operate them, and EPCs do not always have experience of operating and maintaining plants, so why would you trust them to know what spares you need? Asking the vendor how he calculated the failure rates in your application gets an interesting range of answers, if you get one at all, although when you ask him if he will take back all his recommended spares that you have not used in five years’ time, you usually get the same answer! To be fair some major manufacturers do track component failure rates in the field, but they are few and far between.

Whoever decided to list the “two years recommended spares” on the SPIR? How many plants are designed for a two-year life? As a materials manager working with the maintenance team, I simply want to know all the maintainable items required for the life of the equipment. My task is to determine the spares required to keep the revenue producing assets running for the life of the plant.

Commissioning spares is another column frequently found on SPIR documents. Before you buy the commissioning spares check with the EPC, they will probably be responsible for these spares during the commissioning period and will be leaving you a mountain of unused spares, and will usually be asking a silly price for them on handover. As an owner operator, you will be in danger of overloading your warehouse with spares you might never use or have already purchased.

I do not want to spend subsequent years repeating the exercise to find out what spares I do not have, or which spares I will never use, you know, those spares that were purchased “just in case”.

When reviewing SPIR documents in order to determine the spares required for the operation, the criticality of the equipment, the maintenance capability, and an understanding of the planned consumption also need to take into account. Furthermore, a number of organisations have strategies to run certain non-critical equipment to failure and then replace the complete unit rather than repair the item using the recommended spares. This information is, understandably, not on the SPIR form but is vital in the decision-making process.

It never ceases to amaze me seeing a room full of people analysing SPIR forms and ordering the spares listed – using the helpful column added by the vendor – without taking these factors into account.

I have carried out many studies of MRO inventory for companies around the globe, and the two most frequent causes of non-moving stock is spares purchased for equipment that is no longer exists, and more commonly, spares purchased for equipment where the plant maintenance capability does not exist to repair and item; motor and pump spares are the favourites. It should go without saying that there is no point in keeping a bearing for a motor in a zoned area for your repair shop to use if the repair shop is not approved to complete work to that standard, or does not have a facility to test the repaired equipment. Pump and motor spares are most frequently purchased and remain unused, as most often the maintenance strategy is to send these units out for refurbishment when they fail. So why were they purchased in the first place? Probably because they were very helpfully listed on the SPIR and the buyer has taken the easy route of taking the word of the manufacturer regarding the required spares or they have purchased the spares as part of a package.

In the age of international digital data exchange standards such as ISO 8000, it is frankly mad that people are still using these outdated methods of creating and distributing the vast amounts of data required for large projects. This spreadsheet has to be distributed through a laborious process and takes months if not years to reach its intended target, when it could be available to all parties instantly using a simple data exchange service.

There is a paradigm shift using new technology and international standards such as ISO 8000. The traditional process of the buyer creating templates to describe an item that fulfils a fit, form, or function as a method of identifying substitutable goods or services, is being replaced with the importing of supplier catalogue items created using specifications defined by the supplier in a computer interpretable format. This new process reduces the cost of handling such data, thus increasing the quality of the data, and importantly, establishing the provenance of the data.

A simple clause in the contract with the EPC would save all this waste:

“The supplier shall supply technical data for the products or services they supply. Each item shall contain an ISO 8000-115 compliant identifier that is resolvable to an ISO 8000-110 compliant record with free decoding of unambiguous, internationally recognized identifiers.”

About the author

Peter Eales

Chief Executive MRO Insyte

Peter Eales is a subject matter expert on MRO (maintenance, repair, and operations) material management and industrial data quality. Peter is an experienced consultant, trainer, writer, and speaker on these subjects. Peter is recognised by BSI and ISO as an expert in the subject of industrial data. Peter is a member ISO/TC 184/SC 4/WG 13, the ISO standards development committee that develops standards for industrial data and industrial interfaces, ISO 8000, ISO 29002, and ISO 22745, and is also a committee member of ISO/TC 184/WG 6 that is developing the standard for Oil and Gas Interoperability, ISO 18101.

Peter has previously held positions as the global technical authority for materials management at a global EPC, and as the global subject matter expert for master data at a major oil and gas owner/operator. Peter is currently chief executive of MRO Insyte, and chairman of KOIOS Master Data.

Peter also acts as a consultant for ECCMA, and is a member of the examination board for the ECCMA ISO 8000 MDQM certification.

ECCMA is a membership organization and is the project leader for ISO 22745 and ISO 8000 KOIOS Master Data is a world leading cloud MDM solution enabling ISO 8000 compliant data exchange MRO Insyte is an MRO consultancy advising organizations in all aspects of materials management